Interview with Mexican Egg Donor & Artist, Paola Livas

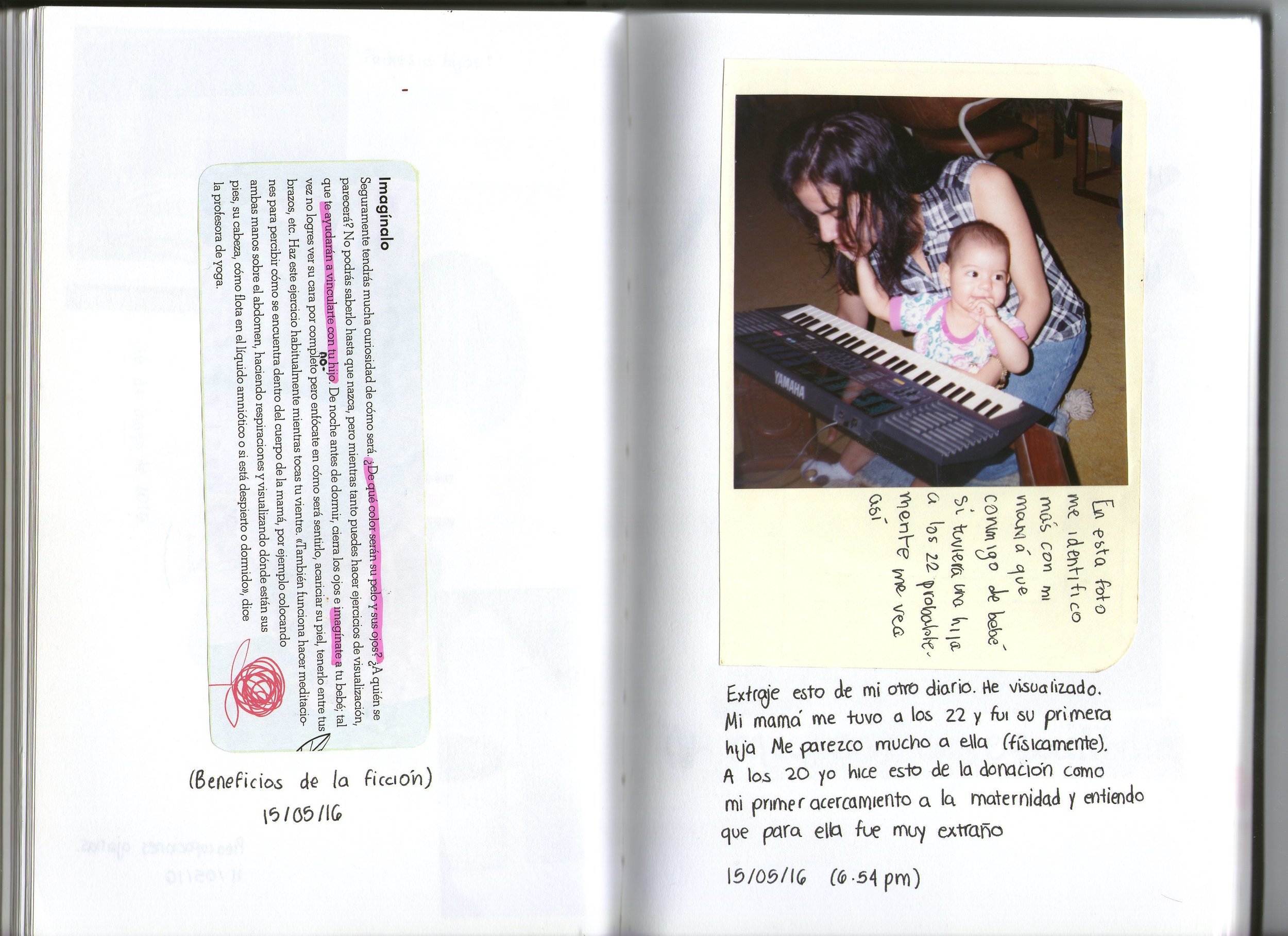

Paola Livas is a Mexican installation artist and writer whose work focuses on her personal experiences. In this interview, Paola shares her experience donating her eggs in 2015 in Monterey, Mexico when she was nineteen years old. We also excerpt from her visual art project, and the journal she kept during the project.

WE ARE EGG DONORS: What were some of your initial thoughts when you donated your eggs?

PAOLA: At first I thought I’d be very detached from everything. “I thought I’d look at is as a normal menstruation cycle, it won’t affect me at all, I won’t have any attachment to the eggs that I’ll be giving away.

As I went on, I realized that I started to ask myself questions about maternity -- ‘Who will be the mother?’ I didn’t want that role. I was giving it away to another woman, and I thought a lot about what the other woman represents to me. What will I represent to them? I will always be this invisible person who was involved in the birth of their child. I always thought of it as a possibility but...

It brought up a lot of questions about maternity and the possibility of a child. I started making a fiction out of it. I even made a name for him and her. In Spanish, it was quite hard to find a concept for the whole thing that I was going through. I had this rejection that the baby would not be mine; it was a statement in my mind: The child conceived will not be your child. That was in my head. I made up term, Mi No-Hijo/No-Hija (my Non-Child), I didn’t want to let go of the link with this possible human being, but I didn’t want to give myself the role of mother or anything like that. That’s why the term came up. It was very comfortable for me. That ambiguity gave me ease. The term helped.

WAED: Did your feelings change over time?

As time passed, it got to the point where the baby had been born. Nine months passed. My concerns started to materialize themselves because I felt there was a real baby out there. I started writing letters and messages into baby clothes because it was easier for me to make connection. To show people that this could be a reality.

The whole project started with these crazy feelings up and down and it developed into a sense of responsibility for the child, because I keep thinking about this generation of people who are born under these procedures and what kind of identity crisis or questions might they have when they find out that there was another person involved in their creation? Will I look like them? Kinship and other aspects that they become very blurred. I was concerned about that and that’s when I started writing messages and letters. If the baby finds me as his donor, he can look back and I'll show him or her the letters and messages. They will know that donating my eggs was not something irrelevant for me; it was something that stuck to me and made me reconsider everything in my life.

Now I’m trying to move forward to asking myself some of the background questions — some of the political aspects that come with egg donation and surrogacy and the power of one body over another, just because they have the money to do this, and what we as donors do when we come into this structure.

WAED: Did you feel a power imbalance when you were a donor?

PAOLA: When they mentioned the other woman… I was thinking more of the empathy towards the other woman who really wanted maternity. That was the thing that was more important to me at the moment. Of course I felt scared, I didn’t have moral support with me. My boyfriend at the time was going with me to the extraction, he was there at some points, but that was the only support there in the process. I did feel scared. When I was there at the table, I blacked out and came back again and I was like "what just happened"? Of course they didn’t give me any information. They said it went fine. I felt like a guinea pig, but I felt like I trusted them as an institution, I'm still scared but I put my body through this voluntarily. At one point I wanted to back out.

WAED: Why did you want to back out?

At some point in the process I really wanted to quit. I was doing this all by myself. I was already ‘legal’ and old enough to make this choice. I went into it by myself. All of the appointments, I went by myself, and I never told my mom or my dad or any family member until I was about to have the extraction. I knew that there would be opposition and they would talk me out of it. I was very determined at first. I really thought that it was something that I was going to do by myself and face everything myself. All of that became very overwhelming because I wasn’t able to tell my parents. I started having Big Questions. Through the process, doing this in ‘secret’ mode was becoming too much. “Are you sure, you really sure you want to do this?” I asked myself over and over again. I had a meltdown or something. I told the clinic I was unsure, I talked to them about the possibility of quitting: They told me that quitting is no longer possible.

The doctors told me that at that point, I couldn’t quit, because "they already had a recipient synced up with me". They told me that I couldn’t quit.

At that point, it sank in, I realized that it wasn’t happening, my eggs are really going to a woman. They were going into another woman’s body and she was trying to get pregnant and have a baby born from it. It felt crazy.

WAED: It's unsettling to hear that you were denied the right to revoke your consent. Is it because you had a contract in place?

PAOLA: It wasn’t a contract — it was a document with the steps to follow, a medication protocol: on this date, you take this med, and on this date you come in for an extraction. It wasn’t a signed document that says “I accept that I have to donate my eggs and I will never know…” There was no signed document. It was a medication instructions form.

WAED: Had you started the injectable medication yet?

PAOLA: No, I think I was still on the pill.

WAED: What was donating your eggs like?

PAOLA: They didn't tell me how many eggs were retrieved, but I did get Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome. It was really bad. It was really horrible. After the extraction, I felt good the same day. I got hamburgers, I felt good. But that was finals week in school. I take school very seriously. They told me I should rest but I told them that I won’t stop going to school and delivering my papers, and getting good grades, I tried to do both, and I was very bloated and feeling very dizzy and nauseous, I had a headache, I had problems breathing. I went to the hospital and they went me to the same hospital where I donated, and they took care of it. It got to the point where they had to carry me in a wheelchair. I couldn’t move, I was very tired. I was pale, I was vomiting all the time, it was very bad. I felt like I was the one who got pregnant. My stomach was up to ‘here’ — in my diary, I kept writing that I couldn’t breathe. I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe. My mother came along and I had to spend three nights in the hospital. They kept the hydrated and gave me medication. I was monitored very closely.

WAED: What is the egg donor compensation like in Mexico?

PAOLA: I remember doing the math, in Mexican pesos, it was 15,000. If you switch that into dollars, it's very very little. [806.400 USD]

WAED: Your exhibition had childrens clothes with writing on it. What are some of the messages?

PAOLA: There’s one that says “You will always be with me, in my thoughts, in my memories, in the idea that you may exist.” It’s hard to translate. I wrote one letter on Mother’s Day, the exhibition opened on Mother’s Day. It was important to me to give this a lot of visibility. It’s not as widepread as is in the United States. People were shocked. I got negative comments “Did you even know what you were doing?” But mostly the public — the people that go to the shows, they are shocked, and they never considered it as a possibility. When I show them the proposal of where I’m going, they start thinking about the concepts like identity, what’s going to happen with people, what will happen with donors, and mothers, and all of that. It’s very important to me. That’s why I did it on Mother’s Day.

WAED: Tell us about the future of your project.

PAOLA: I’m trying to move away from all of this very sentimental part of the project, because of all of this, the messages — it evokes a lot of feelings. I feel like I’ve poured them all. I want to focus on the research and the bigger questions that I was telling you about: Let’s talk about the power one woman has over a woman to have a baby of her body, and that baby will be hers, and the ‘backstage dynamics’ per say and not focus on my experience. This whole time I’ve been focused on me — my family, my pictures — now I want to look at the big picture.

WAED: What else should we know about your art?

PAOLA: I’m doing an interview to myself every five years. Same questions, but I ask them to myself every five years, I keep going back into it, to see if I still thinking about maternity the same way, or if I think about Mi No-Hijo/No-Hija (my Non-Child) and all of this.